Part 2:: Review of the socionic model of information metabolism at individual, interpersonal and societal levels

Nov 14, 2024

3. Model A

3.1 Introduction

Augustinavičiūtė decided to integrate Jungian model of the psyche with Kępiński’s model of IM (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998a). In her model, four Jungian functions of consciousness were combined with two attitudes (extraversion/introversion) to give eight cognitive functions, similarly to the MBTI model (Myers, 1962, 1980). The original MBTI model assumed existence of eight different cognitive functions (Fi, Fe, Ti, Te, Si, Se, Ni, Ne) of which everyone possesses only four, each assigned to one of four possible positions (i.e. dominant, auxiliary, tertiary, inferior). The positions described the level of competence and the degree of consciousness of each function (the further the position, the less conscious the function). Jung mentioned that the most complete understanding of phenomena is reached if they are investigated by all four functions of consciousness (i.e. sensation, intuition, feeling and thinking) (Jacobi, 1968). The MBTI model lacked a clear explanation of how the functions cooperate. Augustinavičiūtė, on the other hand, proposed an intuitive mechanism explaining the cooperation of psychological functions. It was her own understanding of information metabolism, inspired by Kępiński’s concept, but not exactly the same. Her idea will be discussed further in this section.

Carl Jung distinguished eight basic psychological types, based on their dominant funtions and conscious attitues towards reality (Jung, 1921). From Jung’s work, it is known that each of eight Jungian types percieves the world differently (Jacobi, 1968; Jung, 1921; Pascal, 1992). Based on that observation, Augustinavičiūtė proposed that information may be divided into eight aspects or types. Before we proceed with the introduction of these eight aspects of information, it is worth to mention about the distinction between information aspect and information element proposed by Augustinavičiūtė (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998b). According to that distinction, information aspect is the property of the objective reality (things-in-themselves). By contrast, the term information element refers to the reflection of the objective reality, processed by subject (in the psyche and the nervous system). The case of Augustinavičiūtė’s definitions of information elements and aspects is complicated, as she suggests that information allowing to identify 9 objects exists independently of observers (see below). Considering the discussion presented in section 2, it must be noted that boundaries between objects are established subjectively. Therefore, in the present article, only the term information element will be used, as referring to the qualities and processes existing in connection with the observer. To avoid misconceptions, the term information aspect will not be used. Let us enlist the eight elements of information, as defined by Augustinavičiūtė (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998a). These are:

- implicit statics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted intuition;

- implicit statics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted intuition; - explicit statics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted sensation;

- explicit statics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted sensation; - implicit dynamics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted feeling;

- implicit dynamics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted feeling; - explicit dynamics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted thinking;

- explicit dynamics of objects – related to Jungian extraverted thinking; - implicit dynamics of relationships – related to Jungian introverted intuition;

- implicit dynamics of relationships – related to Jungian introverted intuition; - explicit dynamics of relationships – related to Jungian intorverted sensation;

- explicit dynamics of relationships – related to Jungian intorverted sensation; - implicit statics of relationships – related to Jungian introverted feeling;

- implicit statics of relationships – related to Jungian introverted feeling; - explicit statics of relationships – related to Jungian introverted thinking.

- explicit statics of relationships – related to Jungian introverted thinking.

3.2 Element Dichotomies

3.2.1 Objects and Relationships

It may be seen that the definitions of information elements are constructed using three dichotomies – objects/relationships, statics/dynamics and implicit/explicit. Before elaborating on each element separately, let us discuss these dichotomies. As mentioned before, reality is experienced by humans as a collection of stimuli or objects whose boundaries are established in the nervous system of the observer. The experience of these objects is such, that they can be related, i.e. compared. There is a qualitative difference that allows to distinguish them. For example, one’s subjective feeling experienced in a given moment towards some object or person, may be distinguished from the subjective feeling experienced towards some other object or person. The other example might be comparing the subjective experience of a rain drop falling on our forehead with that of being hit by a stone.

One can imagine an organism with sensory receptors in which the signals from these receptors are not integrated in a meaningful way, but rather processed chaotically. The probability of survival of such organism would be very low. It would increase if the organism was able to distinguish moving objects, i.e. predators, from the background noise, and respond with appropriate actions. Fortunately, photoreceptors allow us to distinguish color (there are different types of cone cells for basic colors) and luminance (encoded in the frequency of action potentials) (Niven, Anderson, & Laughlin, 2007), 10 which gives the nervous system a necessary basis for distinguishing objects from their background. Similar analyses may be performed for other senses, but vision is of paramount importance. Therefore, the processing of signals in our bodies is such, that separate objects are distinguished. In case of humans, due to the complexity of our brains, objects may not only be material, but also abstract and complex, i.e. ideas, imagined objects, universals etc. (Russell, 1912).

It seems necessary to answer why Augustinavičiūtė decided to rename Jungian extraversion/introversion dichotomy to objects/relationships. According to Jung, the dichotomy was made to distinguish between subjective and objective attitude towards reality (Jung, 1921). Even though all experience is subjective, Jung found that some people prefer one attitude, while others prefer the other. The distinction is based on the degree to which perception or judgement of objects is influenced by subjective and idiosyncratic contents of the subject. Objective (extraverted) attitude is characterized by the submission of the subject’s perception to the experienced objects. Introversion, on the other hand, is characterized by greater distance between the object and the subject. In the mind of an introvert, all external phenomena are interpreted in relation to the internal (i.e. inborn, originating in the subject) contents of the psyche. Those internal contents are given a superior position. That is opposed to the conscious mind of the extravert which ascribes superior role to external objects.

Talanov proposed a model according to which the conscious metabolism of information in extraverts is ihibited by low intensity stimuli and excited by strong stimuli (Talanov, 2006). This model suggests that extraverts need strong external stimuli in order to orient themselves in the world. The internal stimuli (interoception, daydreaming) are presumably not enough to them. Information metabolism of introverts, on the other hand, is inhibited by strong stimuli and stimulated by the more subtle ones. Therefore, introverts are more likely to concentrate on the internal stimuli which are produced in response to external excitations, and not on the external excitations themselves. Let us notice that such internal stimuli express the relationship between the introvert and the external world, which explains how introversion is linked with the perception of information about relationships.

3.2.2 Statics and Dynamics

Next dichotomy that needs to be explained is statics and dynamics. Reality is experienced as a process of transient nature. Change is inevitable and inherent to consciousness. It is hard to study the nature of objects in motion. To overcome this obstacle, it is necessary to immobilize the object. A child might want to immobilize the butterfly to learn what it is (Fromm, 1941; Kępiński, 1978). Humans create static models of other people and phenomena, which allow them to orient themselves and undertake appropriate reactions i.e. withdraw or engage in further interaction. Kępiński noticed that in order to compare or distinguish multiple objects, one must freeze them in thought, treat them as collections of static properties (Kępiński, 1978). In that case, attention is directed to those aspects of these objects that are stable. Relationships may also be analyzed from two different 11 perspectives – the perspectives of changing and stable characteristics (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998a).

3.2.3 Implicit and Explicit Information

The difference between explicit and implicit information is best explained by considering Jungian sensation and intuition, or the difference between what is given directly and what is not. An extraverted sensing type focuses directly on the sensations induced by the object i.e. colors, shapes and tactile sensations. An intuitive type also percieves the object, but instead of immersing into direct sensations given by it, he or she explores the possibilities invoked by that experience (Jung, 1921). It should be reminded that the number of ways in which boundaries between objects may be drawn is practically infinite (Peterson, 2013). Even if these boundaries are drawn, the number of relationships formed between each object and other objects is also infinite. At the same time, the position of the object in the network of relationships is what defines its meaning. Intuition allows to access that complexity and make use of the less obvious connections between objects, using the knowledge that comes from the unconscious (Jung, 1921).

The case of thinking and feeling is similar to that of sensing and intuition. The judgements of thinking are relatively understandable, as their logic can be followed by the conscious mind. Feeling, on the other hand, represents older, and therefore subconscious, mechanism (Kępiński, 1974). The subconscious character of feeling makes its judgements mysterious, but it does not prevent feeling types from relying on that function in their conscious decisions (Jung, 1921).

3.3 Descriptions of Eight Elements of IM

The information metabolism elements (IMEs) were discussed in (Pietrak, 2018), however, their brief characteristics will be given here for the convenience of the reader, and to maintain the continuity of thought in this document. These elements are related to different areas of human perception and competence as follows:

- implicit statics of objects - perception of hidden potentials of objects, the possibilities that are inherent in them;

- implicit statics of objects - perception of hidden potentials of objects, the possibilities that are inherent in them; - explicit statics of objects - perception of the external appearance of objects, visible characteristics, strength (how strongly they affect the senses), beauty and level of motivation;

- explicit statics of objects - perception of the external appearance of objects, visible characteristics, strength (how strongly they affect the senses), beauty and level of motivation; - implicit dynamics of objects - perception of changes of internal states of objects (e.g. how their level of motivation/readiness/arousal/mood changes);

- implicit dynamics of objects - perception of changes of internal states of objects (e.g. how their level of motivation/readiness/arousal/mood changes); - explicit dynamics of objects - perception of work done by the objects (i.e. how they move and act in space);

- explicit dynamics of objects - perception of work done by the objects (i.e. how they move and act in space); - implicit dynamics of relationships - perception of changes of indirect, less obvious relationships between objects (i.e. distant interrelations, hidden/background connections);

- implicit dynamics of relationships - perception of changes of indirect, less obvious relationships between objects (i.e. distant interrelations, hidden/background connections); - explicit dynamics of relationships - perception of changes in directly observable relationships between objects (e.g. cause and effect relationships);

- explicit dynamics of relationships - perception of changes in directly observable relationships between objects (e.g. cause and effect relationships); - explicit statics of relationships - perception of logical structures (results in the ability to classify objects based on their properties, think in terms of systems and identify these systems, comparison of objects based on their explicit/measurable characteristics);

- explicit statics of relationships - perception of logical structures (results in the ability to classify objects based on their properties, think in terms of systems and identify these systems, comparison of objects based on their explicit/measurable characteristics); - implicit statics of relationships - perception of attitudes of objects towards each other, their mutual attraction or repulsion (results in the ability to understand social interactions and participate in them).

- implicit statics of relationships - perception of attitudes of objects towards each other, their mutual attraction or repulsion (results in the ability to understand social interactions and participate in them).

3.4 Mechanism of Information Metabolism

The most interesting contribution of Augustinavičiūtė is the idea of the hypothetical mechanism of information metabolism which arises by combining the elements of information into metabolism chains and rings. Its core principle seems easy to understand if few examples are considered. Let us imagine that a person possesses extraverted sensation as dominant function ( element in socionics). According to Augustinavičiūtė's definition,

element in socionics). According to Augustinavičiūtė's definition,  is the perception of explicit statics of objects, as described in previous section. Such perception may be described as taking a still snapshot of an object and identifying its explicit, most certain characteristics. If information about multiple objects is obtained, then they may be compared i.e. their relationships may be determined. In such way, one may determine the relationship between: (a) their static properties i.e. how they are related logically (what type of structure they form, how can one classify them - this is

is the perception of explicit statics of objects, as described in previous section. Such perception may be described as taking a still snapshot of an object and identifying its explicit, most certain characteristics. If information about multiple objects is obtained, then they may be compared i.e. their relationships may be determined. In such way, one may determine the relationship between: (a) their static properties i.e. how they are related logically (what type of structure they form, how can one classify them - this is  ) or (b) their implicit relationships (what are their attitudes toward each other -

) or (b) their implicit relationships (what are their attitudes toward each other -  , which typically refers to living beings, but may also concern personified inanimate objects). The type of information produced in such manner, depends on the type of the auxiliary function of the individual (introverted thinking or introverted ethics). A similar production of information may occur if the direction is reversed. If an introverted type with dominant thinking or feeling builds a matrix of relationships between various objects, he or she can determine the static characteristics of these objects resulting from these relationships.

, which typically refers to living beings, but may also concern personified inanimate objects). The type of information produced in such manner, depends on the type of the auxiliary function of the individual (introverted thinking or introverted ethics). A similar production of information may occur if the direction is reversed. If an introverted type with dominant thinking or feeling builds a matrix of relationships between various objects, he or she can determine the static characteristics of these objects resulting from these relationships.

These examples illustrate the meaning of information metabolism in socionics. It involves producing new information within the psyche based on preceding information, but only in agreement with certain rules. First of all, it is possible to create information metabolism chains made of alternately arranged object and relationship elements of information. However, in such chains, it is impossible to obtain static element from a dynamic one, and vice versa. The justification for that principle becomes clear after considering the following example. Let us suppose that we want to obtain information about the dynamics of some object (its changes), based on the information about static relationships in the 13 network of relationships to which that object belongs. Dynamic information may be conceptualized as anologuos to a video, while static information is like one frame of that video. Therefore, to obtain information about dynamics from the information about statics, one must take multiple subsequent frames. However, an information about a series of subsequent frames is nothing else but dynamic information. Because of that, when considering chains of information metabolism made of various information elements, all elements in a chain must be either static or dynamic.

3.5 Rings of Information Metabolism

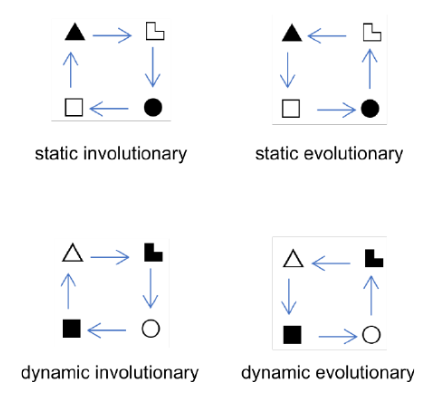

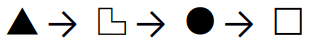

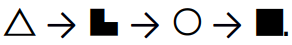

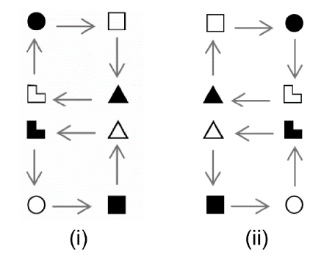

By using principles mentioned in section 3.4, it is theoretically possible to construct infinitely many combinations of information elements, forming information metabolism chains and rings. However, in reference to a human psyche, Augustinavičiūtė narrowed down possible arrangements of information elements to four rings. Each of such rings includes four elements related to four Jungian functions, in accordance with Jung's observation that each individual possesses these four functions, even if they are not equally developed (Jung, 1921). Eight information elements may be connected to form two separate rings - one made of static and one made of dynamic elements. In these two rings, the metabolism may occur in two directions. This gives four basic rings of information metabolism, presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Basic rings of information metabolism

The rings in which the sequence of elements is  are known as involutionary rings, and the rings with the opposite direction of information metabolism (

are known as involutionary rings, and the rings with the opposite direction of information metabolism ( ) are known as evolutionary rings (Gulenko, 2002, 2010). The difference between involutionary and evolutionary order of information metabolism is explained in section 3.9.

) are known as evolutionary rings (Gulenko, 2002, 2010). The difference between involutionary and evolutionary order of information metabolism is explained in section 3.9.

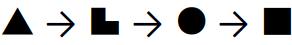

3.6 Structure of Model A

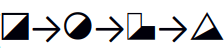

Augustinavičiūtė proposed that human psyche may be presented as two of four basic rings of information metabolism. The model that is obtained in such way, known as model A, was discussed in detail by Pietrak (Pietrak, 2018). There are two basic rules regarding the construction of model A. Both rings of model A should possess the same direction of information metabolism (evolutionary/involutionary dichotomy). One of them should be composed of static elements and the other of dynamic elements (both types of perception are present in our cognition). Augustinavičiūtė also concluded that one ring should describe conscious information metabolism of an individual (the one associated with the dominant function), while the other one, containing the element associated with the inferior function, should be regarded as subconscious (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998a). The number of valid configurations of information metabolism elements in model A is sixteen. These arrangements correspond to sixteen psychological types (Blutner & Hochnadel, 2010; Pietrak, 2018). The number of positions in the functional model of the psyche has been extented by Augustinavičiūtė from four (Jung, 1921; Myers, 1962, 1980) to eight. It is worth mentioning that this model retained positions introduced by Jung (i.e. dominant, auxiliary, inferior) while adding five new positions (role, vulnerable, mobilizing, ignoring, demonstrative; see Fig. 2.). For more detailed descriptions of these new functional positions, see (Pietrak, 2018).

One should note that the socionic concept of psychological function carries the information about the parameters of processing and not about the processed content. Psychological functions may be characterized by three dichotomies (i.e. strong/weak, conscious/subconscious and accepting/producing). These dichotomies will be discussed in section 3.7. The general schematic of model A, including eight psychological functions and their dichotomies is shown in Fig. 2. One should note that pairs of functions in this model form subsystems that may be related with Jungian archetypes (Ego, Persona, Anima and Shadow) (Jacobi, 1968; Pascal, 1992), elements of the Freudian model (Ego, Superego, Id, Superid) (Freud, 1915, 1920, 1923) and internal models of adult, parent and child from Berne’s transactional analysis (Berne, 1964). These associations will be explained in the further sections of the paper.

15 Fig. 2. The model of information metabolism in the human psyche (model A), where: 1 – dominant function, 2 – creative (auxiliary) function, 3 – role function, 4 – vulnerable function, 5 – suggestive (inferior) function, 6 – mobilizing function, 7 – ignoring function, 8 – demonstrative function, A – accepting functions, P – producing functions. The arrows indicate the direction of information metabolism.

3.7 Dichotomies of Psychological Functions in Model A

3.7.1 Accepting and Producing

The basic model of an accepting function is the dominant function. Accepting functions are reproductive. Their aim is to generate an accurate image of the objective reality. By contrast, producing functions generate information which is relatively independent of the objective world. It is secondary information, taken not from the observation of reality, but constructed from the information delivered by the accepting function. For example, in the Ego block of type

(types in socionics are denoted by the symbols of information elements occupying their dominant and auxiliary functions) the information about the potentials of objects (

(types in socionics are denoted by the symbols of information elements occupying their dominant and auxiliary functions) the information about the potentials of objects ( ) is projected to generate information about the explicit statics of relationships between objects (

) is projected to generate information about the explicit statics of relationships between objects ( ). One should note that the essence of the producing function is its ability to create information without making connection to reality. In such function, the connection with reality is established mainly to supplement the produced information, but that information is mainly a product of cognition. Therefore, the producing quality of the psyche may be seen as the most basic mechanism for the generation of new ideas, including memes (Dennett, 1990). “Produced” information is not always useful for its creator or for society, but sometimes it makes a breakthrough. Its usefulness is verified by the mechanisms of natural selection (Dennett, 1990).

). One should note that the essence of the producing function is its ability to create information without making connection to reality. In such function, the connection with reality is established mainly to supplement the produced information, but that information is mainly a product of cognition. Therefore, the producing quality of the psyche may be seen as the most basic mechanism for the generation of new ideas, including memes (Dennett, 1990). “Produced” information is not always useful for its creator or for society, but sometimes it makes a breakthrough. Its usefulness is verified by the mechanisms of natural selection (Dennett, 1990).

3.7.2 Strong and Weak

Jung observed that each individual develops only one of four cognitive functions (intuition, sensing, feeling or thinking) and prefers one of two attitudes (extraverted or 16 introverted). At the same time, some cognitive functions remain weakly developed and archaic. These fundamental observations were expanded upon by Augustinavičiūtė, who translated Jung’s model into the language of her information metabolism model. Consequently, some functions in Augustinavičiūtė’s model A are known to be weak (less effective) and some are strong (more effective). For an in-depth discussion of that dichotomy, see (Pietrak, 2018).

3.7.3 Conscious and Unconscious

The distinction between conscious and unconscious mind was introduced by Freud. The conscious mind is focused mainly around the Ego – i.e. the image of oneself which a person possesses. In socionics, also the Super-Ego is attributed to the conscious mind. The super ego can be considered a separate personality (more precisely Ego and Super- Ego are complexes), a powerful center of influence within the psyche, which makes us aware about our weaknesses and flaws.

Apart from the conscious mind, an existence of the unconscious mind was postulated. It can also be conceptualized as a separate personality within the psyche– the one which compensates for our conscious attitudes. Various contents that were rejected, not accepted by the conscious mind, or perceived subliminally, build the unconscious mind. Freud introduced the Id as the main actor within the unconscious mind. The subsystem of Id has its place in socionics, but socionics also added another subsystem called the Super-Id, which was not mentioned by Freud.

3.8 Model A and Archetypes

Similarly to Freud, Jung considered the psyche as consisting of few centers of influence which he called the archetypes. Some of those archetypes have their corresponding centers in Freud’s model. Technically, the archetypes are also complexes in the Jungian sense, but an archetype may be considered a special type of complex – that is, the one which may be found universally within humans (as opposed to general complexes, which can be unique to given person). The four main archetypes were labeled the Ego, the Persona, the Anima/Animus and the Shadow (Jacobi, 1968; Pascal, 1992). He also identified a fifth archetype - the Self, which signifies the unification of the conscious and unconscious mind of a person and represents the psyche as a whole (Henderson, 1988).

The Ego is considered an archetype describing the identity of the individual and encompassing information that a person is aware of. The Persona also belongs to the conscious mind, but it has a separate place. According to Jung, the true identity of a person is different than what is shown in public. When confronted with society, an individual cannot fully be themself. There must always be some adaptation, a kind of interface between the Ego and society. In relationships, the expectations of other people and the values they appreciate cannot be dismissed, and those may be totally different than one’s own. The Persona symbolizes the compromise we assume in such cases.

It is natural to associate the Ego with the strongest IM functions of the individual. The types of information metabolized in these functions are handled easily and naturally. These IMEs may be regarded as preferred by the subject. It would be perfect if the world also preferred them, but such a utopia would be impossible. The Persona is related to IM functions which are not naturally strong. Interaction with society forces the individual to develop their weaker functions, because in the social flow of information there are no special IMEs. It is easy to encounter a person who prefers to communicate and make decisions using the IMEs placed in their weak functions. Basically, the two strong conscious IM functions belong to the Ego, whereas the two weak conscious functions belong to the Persona (See Fig. 2).

Moving now to the unconscious side, let us consider the types of information we are unaware of during the everyday experience of reality. First, the IME associated with the inferior function of consciousness, the weakest one according to Jung, may be classified as unconscious. In socionics, this function is known as the suggestive function. Its type of unconsciousness resembles blindness, and it affects the producing function cooperating with it (the mobilizing function). The block of these two functions corresponds to the Anima/Animus functional block. In socionics, the Anima/Animus archetype encompasses the forms of perception and reflection that are missing in the Ego, therefore the Ego is subconsciously attracted to it. The assignment of Jungian archetypes to the functional blocks of model A was first proposed by Gulenko (Gulenko, 1998).

Another type of information handled subconsciously is associated with the attitude of the dominant function. It should be remembered that an extraverted function processes information about objects, and an introverted one processes information about relationships between them (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998a). The dominant function assumes one of those two attitudes. Nevertheless, when accepting one type of IME consciously, the other type is simultaneously accepted without being noticed. This is caused by the fact that information about the objects may be translated into information about their relationships, and vice versa. The more we focus on one attitude, the more unconsciously we accept the other. The latter, ignored type of information is gathered and forms the subsystem known as the Shadow. It includes both the ignored counterpart of the IME processed in the dominant function, and the producing function which depends on it (the demonstrative function).

Before moving further, it is important to consider which functions are the main information inputs in the model A. According to Augustinavičiūtė, the 3rd function is the main input in the conscious ring. This is plausible, especially when bearing in mind that the 3rd function is labeled as accepting and weak. We naturally tend to concentrate on the imperfect areas rather than on the well-developed ones. It also agrees with the Jungian view that the exchange of information between the Ego and society is through the Persona. The main information input in the unconscious cycle of IM is function 5 (the suggestive function). This choice becomes clear if we consider that the input to the conscious cycle is through the 3rd function. Functions 3 and 5 process the same type of 18 information, differing only in how they represent information (objects/relationships). As mentioned before, the two are always together, so when accepting an IME to function 3, the 5th function is fed with its coupled version.

The lower ring of model A describes the private sphere of personality and the upper one - the public sphere. The conscious ring plays a fundamental role in relationships. Using its functions, one can consciously help others. More specifically, effective help may be given by one's strong functions rather than by weak ones. For example, a type

individual is able to care for the physical comfort (

individual is able to care for the physical comfort ( ) and moods (

) and moods ( ) of their friends and family. Purposeful actions related to IMEs located in the Persona (

) of their friends and family. Purposeful actions related to IMEs located in the Persona ( and

and  ) are also possible, but they are not very effective (weak block). Let us note that conscious processing implies that its products may be intentionally communicated through speech and writing, unlike information processed at the unconscious level.

) are also possible, but they are not very effective (weak block). Let us note that conscious processing implies that its products may be intentionally communicated through speech and writing, unlike information processed at the unconscious level.

Turning now to the unconscious (vital) ring of IM, it should be noted that its functions are used only for individual purposes. This is the private zone which contains automated mechanisms, the inner workings of which the user is not aware of at the time of execution. Some aspects of processing in the vital ring may be recalled after the fact, therefore Yermak classified the vital ring as preconscious (Yermak, 2009). The term “preconscious” refers to a neural process that potentially carries enough activation for conscious access, but is temporarily held at the unconscious level because of a lack of attentional amplification (Dehaene, Changeux, Naccache, Sackur, & Sergent, 2006).

3.9 Evolutionary and Involutionary Information Metabolism

Two orders of information metabolism - involutionary and and evolutionary - were introduced in section 3.5. They were originally noticed and shortly commented upon by Augustinavičiūtė in her early works on socionics (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998a). According to her hypothesis, the thinking style of the representatives of evolutionary psychological types should be different from the thinking style of the representatives of involutionary types. The issue was later investigated by her and Reinin (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998c; Reinin, 1996), yet their conclusions were rather vague. Both authors mentioned that the dichotomy is not well studied. The most thorough analysis of the two orders was given by Gulenko (Gulenko, 2002, 2010). He based his conclusions on observations made during teaching and socionics consultations, when he had the opportunity to determine the psychological types of various people and analyze their thinking styles. In this article, the findings of all three authors mentioned in this section will be summarized.

Firstly, it is useful to consider the analogy between energy conversions in a heat engine and the metabolism of information, introduced by Augustinavičiūtė (Augustinavičiūtė, 1998a). In this analogy, it is proposed that the activity pattern of human organism arising as response to a stimulus may be divided into four stages:

1 – the state of rest (maximal potential energy),

2 – conversion of potential energy into kinetic (when the organism is mobilized by the stimulus, e.g. a threat, and the body is conditioned to undertake a reaction),

3 – the state of maximal kinetic energy (at the beginning of motion e.g. escape),

4 – the exploitation of kinetic energy, or work (the energy reserves are expended as the reaction is carried out).

The energy changes in an organism may be considered analogous to energy changes that occur in the heat engine:

1 – the state before the compression of the working fluid (maximal volume of the combustion chamber),

2 – the dynamic phase of compression of the working fluid,

3 – the moment of ignition,

4 – the dynamic phase during which the piston is pushed by the expanding gas (and useful work is performed by the engine).

Furthermore, it is assumed that each of these four phases may be assigned a corresponding object-related information element in socionics:

1 –  as the information about the potential energy of objects,

as the information about the potential energy of objects,

2 –  as the information about the conversion of potential energy into kinetic energy,

as the information about the conversion of potential energy into kinetic energy,

3 –  as the information about the kinetic energy of objects,

as the information about the kinetic energy of objects,

4 –  as the information about the exploitation of kinetic energy (compare with explanations in section 3.3).

as the information about the exploitation of kinetic energy (compare with explanations in section 3.3).

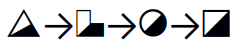

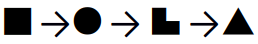

The connection between energy conversions and information metabolism elements is metaphoric, but it helps to understand certain concepts. In the presented analogies, relationship-related information elements were neglected for clarity. Let us now look at models of information metabolism for two psychological types -

and

and

(Fig. 3). The conscious sequence of information metabolism in

(Fig. 3). The conscious sequence of information metabolism in

is

is  and the unconscious sequence is

and the unconscious sequence is  . Let us combine the two sequences and skip relational elements. It gives the following pattern:

. Let us combine the two sequences and skip relational elements. It gives the following pattern:  . It is the pattern corresponding to the presented activity pattern of an organism and energy conversion pattern of the heat engine (1-4). Only eight of sixteen personality types follow that IM pattern, while in the other eight the sequence is reversed. Consider the type

. It is the pattern corresponding to the presented activity pattern of an organism and energy conversion pattern of the heat engine (1-4). Only eight of sixteen personality types follow that IM pattern, while in the other eight the sequence is reversed. Consider the type

in which the reversed sequence

in which the reversed sequence  is apparent (see Fig. 3).

is apparent (see Fig. 3).

20 Fig. 3. Models of IM for types

and

and

. The order of information metabolism in the type

. The order of information metabolism in the type

agrees with the activity pattern of organisms, whereas in the type

agrees with the activity pattern of organisms, whereas in the type

it is reversed

it is reversed

The reversed order of information metabolism follows the energy conversions of a heat pump, in which work is supplied to transfer heat in the direction opposite to the natural (Cengel & Boles, 2006). In natural conditions, heat flows only from warmer to colder environments, but the heat pump can transport heat from a cooler to warmer source. In this way, the potential energy of a thermodynamic system containing both sources is increased.

The analogy between information metabolism and thermodynamics helps to understand the difference between involutionary and evolutionary types. In some sense, the thinking process of involutionary types reflects the heat engine operation and that of evolutionary types may be compared to the operation of a heat pump. In the first approximation, the thought process of an involutionary type is equivalent to what is commonly understood as inductive reasoning (Gulenko, 2002). These thinkers collect observations regarding a complex phenomenon and infer conclusions from the general regularity which emerges from these observations. The direction of thinking is from complex to simple. The details of the image are often neglected in order to mentally grasp its higher-level structure. In such way, involutionary thinkers uncover new potentials existing in reality, and make their application possible. By contrast, evolutionary thinking is deductive. Starting from a set of assumptions treated as strong, these thinkers examine their after-effects. They exhibit a tendency to mentally complicate the situation, therefore evolutionary thinking may be seen as a vector from simple to complex. It can also be seen as extracting potential from the known, instead of the unknown.

These two types of information metabolism are what makes the continual progress of humanity possible. It is obvious that reality is not static, but it always changes, and that change occurs in the direction of increasing entropy (the second law of thermodynamics) (Kępiński, 1974). Therefore, there is always some new information to uncover. The ability of humans to uncover new information results in technological and scientific progress, but more importantly, it sometimes decides about their survival in ever changing 21 conditions. On the other hand, humans and other organisms need the solid base of already established knowledge to interpret new information. At the lowest level of abstraction, their bodies may be regarded as embodied information, or embodied knowledge. At the higher level of abstraction, they possess internal models of reality existing due to the operation of their nervous systems. The ways in which the internal models of reality are updated in humans were studied by Piaget (Piaget, 1970). He distinguished two mechanisms for the integration of new knowledge, which he called assimilation and accommodation. During assimilation, humans acquire knowledge by interpreting a new phenomenon using categories and models that they already understand. Accommodation, on the other hand, occurs when new phenomenon cannot be understood within the current structure of their knowledge and its incorporation requires rebuilding of that structure. It is reasonable to assume that involutionary information metabolism cycle is predominantly related with accommodation and the evolutionary information metabolism with assimilation. The relation postulated here is not identity, but rather an interesting resemblance that should be further investigated.